Presentation by Lalisa Duguma at the ICRAF side event on agroforestry and REDD+ at the Paris COP21

Tag: World Agroforestry Centre

- Home

- Agroforestry and Redd+ in Africa: potentials, challenges and the way forward

|

Posted by

FTA communications |

Presentation by Lalisa Duguma at the ICRAF side event on agroforestry and REDD+ at the Paris COP21

|

Posted by

FTA |

Find out about events related to the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry at the 22nd Conference of Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP22) in Marrakesh, 7-18 November.

Forests and landscapes are set to play a key role in the new global climate and development agenda. The Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) brings the latest scientific research, insights and experiences to discussions held alongside the negotiations. See below for details on CIFOR’s involvement.

The Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) at COP22

Also see two related briefs:

Agroforestry for climate action commitments and the Sustainable Development Goals

A detailed program of ICRAF’s participation at the COP is available at

The World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) at COP22

The Paris climate change agreement came into force on 4 November 2016—an unprecedented event. And the Marrakech climate talks, COP22, will be all about turning that agreement into reality on the ground.

Trees in forests and on agricultural landscapes are central to climate change mitigation and adaptation, and to delivering on the Paris Agreement.

Agroforestry—agriculture with trees—is also instrumental to reaching the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that aim to eradicate hunger, reduce poverty, provide affordable and clean energy, protect life on land, reverse land degradation and combat climate change. Because of the carbon sequestration capacity of trees, agroforestry can contribute to countries’ reaching their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) is supporting national governments in Africa, Asia and Latin America in developing the tools, knowledge and capacity needed to successfully scale up sustainable agricultural solutions. We call for:

Scaling up agroforestry as a solution for climate change adaptation and mitigation via Nationally Determined Contributions;

Raising the investment in providing scientific evidence of agriculture’s contribution to climate change mitigation and adaptation;

Reducing land degradation and deforestation through agriculture with trees; Including sustainably produced bioenergy to the Sustainable Energy for All (SE4ALL) initiative’s portfolio of options to end energy poverty.

ICRAF will co-host three events at the Marrakech COP22:

Innovation and deployment of technologies for climate change adaptation with support from the Climate Technology Centre and Network, event with Technical University of Denmark, DTU, at the Africa Pavilion on Friday 11 November from 12:00-13:30.

Woody Biomass Energy to Meet NDCs and SDGs in Developing Countries, side event with International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (INBAR) on Tuesday 15 November 2016 from 16:45-18:15; and

From commitment to action – developing strategies to operationalize integrated landscape approaches, event with CIFOR at the Global Landscapes Forum on Wednesday 16 November 2016, from 11.30-12.30.

|

Posted by

FTA |

By Joan Baxter, originally published at ICRAF’s Agroforestry World Blog

It’s a tall order solving the myriad developmental challenges in North Kivu Province in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where years of conflict have caused so much human suffering and environmental upheaval. Today the province is plagued by rampant deforestation and land degradation and hence low agricultural production, while also having to cope with high population densities and urbanization rates.

These can all be tackled, according to the provincial Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries, Livestock and Rural Development, Christophe Ndibeshe Byemero, if agroforestry forms the basis for a strategy for sustainable agricultural development.

The Minister was speaking at a workshop held earlier this year in the provincial capital, Goma, to examine ways to develop and expand agroforestry in the area. Organized by the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). The workshop brought together 46 participants from a wide array of local, national and international organizations, with strong representation from civil society groups from many parts of the Province. It marked the culmination of three years of agroforestry research in development in the region that aimed to develop a socially inclusive strategy for scaling up agroforestry and tree diversity.

According to Thierry Lusenge of WWF in the DRC, the time is now ripe to recognize the importance of agroforestry in helping populations adapt to and mitigate climate change, reduce deforestation and improve food security.

Looking back and learning…

The workshop was the last of three held in the region as part of the project, Forests and Climate Change in the Congo (FCCC), funded by the European Union and led by the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). The agroforestry component of the FCCC project, led by ICRAF, was a part of the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry.

It built on the knowledge gleaned from previous workshops and acquired through interviews with diverse groups in the area, bringing together participants from four territories in North Kivu. Participants looked back at their agroforestry accomplishments over the past three years and at lessons learned from the diverse projects they’d been part of.

Deogratias Mumberi Kyalwahi of the women’s conservation group, Femmes Actives pour la Conservation de la Faune et de la Flore (FACF), presented findings from a project to establish agroforestry and improve agricultural production around the city of Beni, as a way of reducing human encroachment in the neighbouring Virunga National Park.

Virunga is a World Heritage site that boasts 2,000 plant species as well as endangered animal species including the iconic mountain gorilla.

Fataki Baloti, representing the youth conservation group Jeunes pour des Ecosystèmes décents et l’Assainissement de la Nature (JEAN), spoke of their work to achieve food security and combat malnutrition, by integrating livestock production and agroforestry, which improved relations between local people and the Congolese wildlife authority, Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature (ICCN), which is responsible for the national park.

Improved human welfare around the park, with more – and more diverse – tree cover that provides income, environmental services and contributes to food security, is critical for preserving the park and for peaceful, constructive interactions between nature conservationists and local people.

Other participants highlighted peri-urban agroforestry projects around Goma to combat poverty and malnutrition – introducing shade trees in coffee systems in the Beni territory, trees for improving soils in Rutshuru territory, and promoting raising and selling tree seedlings in Lubero and Kirumba towns.

Emilie Smith Dumont of ICRAF explained that agroforestry “while not a panacea, can contribute to making livelihoods and landscapes more sustainable”. She emphasized that it involves many different practices suitable for different people and places, such as planting trees on contour slopes, establishing windbreaks for pastures or fodder banks, fruit trees in orchards and homegardens. These include diverse tree species adapted to different environments and to specific needs of the farmers themselves.

Removing barriers to adoption

Participants agreed that while significant progress has been made in collecting information on promising native tree species for agroforestry in the region, and in developing practical tools, including a technical agroforestry guide that helps people to put agroforestry knowledge into practice, some key changes in policy and practise are needed for further agroforestry expansion and development in the region.

They identified seven major issues that need to be addressed in an integrated way – gender, markets and commercialization, governance, availability of and access to quality tree planting material, improving agroforestry know-how given low literacy rates, threats such as fire and pests, and, cultural realities.

Gender and tenure at the fore

Women farmers trade at the evening market in Kitchanga, Masisi, North-Kivu, after a day in the field. Many members of the community are internally displaced and farming marginal land with no tenure security.. Photo by E Smith Dumont.

Two issues – tenure and gender – emerged as perhaps the most pressing constraints. On theissue of gender, Vea Kaghoma of the league of women’s smallholder organizations in DRC, Ligue des Organisations des Femmes Paysannes du Congo, was adamant and unequivocal. Speaking at the closing of the workshop, she said women, who constitute the majority of farmers and traders, should be at the heart of all agroforestry efforts in North Kivu and that the participation of women’s organizations is indispensable if these efforts are going to succeed.

Emilie Smith Dumont of ICRAF concurs. “Without secure land tenure, especially for women, it is difficult to progress to the next step of really scaling up agroforestry in DRC,” she says. Farmers cannot begin to envisage making long-term investments in their land health or in tree planting if they do not have secure access to land.

Spreading the word

Dumont Smith is greatly encouraged by the momentum that emerged from the workshops, and at on-going work by participants to put into practise what they have learned over the past three years.

Wilson Kasereka Kabwana, president of a group to support and consolidate peace and development in North Kivu (Programme d’Appui à la Consolidation de la Paix et le Développement or PACOPAD), reports that his group has now developed a nursery for several agroforestry species. They work with local communities and schools to spread the word on their value for nutrition, as medicine or for the environmental services they provide.

Mone Van Geit, Project Manager International Programs, WWF Belgium, says the idea is to continue to cultivate the strong partnerships that were forged during the FCCC project, with strategies that will permit WWF to support local communities in diversifying species and practices to address a broader range of stakeholder needs. When it comes to energy woodlots, which she says remain a key priority for WWF around the park, diversification and inclusion of native species will be high on the agenda. This will require innovative approaches to test mechanisms for incentives and trials for species carefully designed and evaluated.

Fergus Sinclair who leads the systems domain at ICRAF said he hopes that ICRAF, WWF, their partners in DRC, and new ones with an interest in tenure, gender and markets, will be able to secure support for multidisciplinary projects that will build on the foundation laid by FCCC and act as the launch pad for agroforestry development in the region.

In the words of the provincial minister, Christophe Ndibeshe Byemero, in ten years, if partners continue to work together, North Kivu could become a veritable “model of agroforestry”.

For more information on this work, please contact Emilie Smith Dumont: e.smith@cgiar.org

Workshop report: http://www.worldagroforestry.org/output/north-kivu-report-workshop-drc

More about ICRAF’s “research in development” approach can be found in these two blogs: One small change of words – a giant leap in effectiveness! and For every tree a reason — research “in” rather than “for” agroforestry development

More about the FCCC project can be found in this blog: Outside a national park, agroforestry helping to save forests inside the park.

More about the technical agroforestry guide developed for North Kivu as part of the FCCC project: Beyond eucalyptus woodlots: what’s on the agroforestry menu for communities around Virunga? The technical guide (available in French only) is available here: Guide technique d’agroforesterie pour la selection de la gestion des arbres au Nord-Kivu

|

Posted by

FTA |

The CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA) is entering its next phase in 2017; this is an opportunity to take stock of the partnerships that made this research program a success and to look at the new partners who will come on board. In several upcoming blog posts and interviews, we are showcasing partnerships that can serve as examples, in the knowledge that it took hundreds of partners to make it work: donor agencies, research institutes and universities, government bodies, nongovernmental organizations and farmers on the ground. For our first blog, we asked the previous FTA Director Robert Nasi about the FTA partnership model and what worked well. You can find more stories on partnerships here.

Partnerships are key to the delivery pathways of FTA; also we have many different levels and types of partnerships within the program, spanning research, capacity development, outreach, implementation, and more.

The core management partnership is between the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Agricultural Research for Development (CIRAD), Bioversity International, Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center [Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza], (CATIE), the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) and the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF).

This partnership has been effective although we had a rather difficult starting point in 2011 when centers were essentially competing for leadership of the different Research Programs.

Also read: CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry has new Director

Developing and implementing FTA research gave us the opportunity to sit and plan together, to exchange knowledge and ideas and to learn to value each other. And now, after five years, we can see an increased level of solidarity between partners in developing and getting over the various hurdles during the joint preparation of the proposal for the next phase.

We can honestly say that we have moved from a competitive to a more collaborative approach. Of course there still is and will be some level of competition because of the nature of the work and the funding context but we are becoming more and more collaborative in our fundraising efforts.

We now have a mature partnership so we can address hard issues up front and solve them together. For me, this is real success and proof of a real partnership.

New partners joining

The fact that new partners, such as Tropenbos International and the International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (INBAR) want to join us demonstrates the value and reputation of the FTA as a partnership. They want to come on board as core partners for the new phase because they are interested in the research agenda and because FTA as a program adds value to their work. Partners are interested because of the things we do and because of the added value of being part of an integrated effort more than for the prospect of getting a huge amount of money.

Bigger than the sum of its parts

We have developed specific partnerships within FTA that are bigger than the program, for example the Tropical managed Forests Observatory (TmFO), led by CIRAD which has 22 institutions working in it. The Partnership for the Tropical Forest Margins (ASB) and the Sentinel Landscapes project are other partnerships within FTA.

Working through the difficulties

During the last 24 months, we have had some issues with commitment to our partners because of unplanned budget cuts but thanks to the maturity of the partnership we have managed to overcome these and keep people on board (even after cutting their budget by more than 50% in some cases).

There is still some room for improvement. It is not always easy for people in one institution to understand what is happening in another in terms of budget management or internal procedures. It is often challenging for non-CGIAR partners to respond to specific CGIAR requests.

This has created some practical issues, but we’ve always managed to sort it out. So, all in all, FTA in a short number of years and in a difficult budget environment, has managed to gather up six competitive organizations at the top of their field in forest, trees, agroforestry and land use research, to work together in a real collaborative way. And the decision by the CGIAR System Council to continue this vast integrated program for another six years confirms that FTA phase 1 was a real success story.

Long-term relationships and mutual trust—partnerships and research on climate change

The best science is nothing without local voices: Partnerships and landscapes

Influence flows both ways: Partnerships are key to research on Livelihood systems

|

Posted by

FTA |

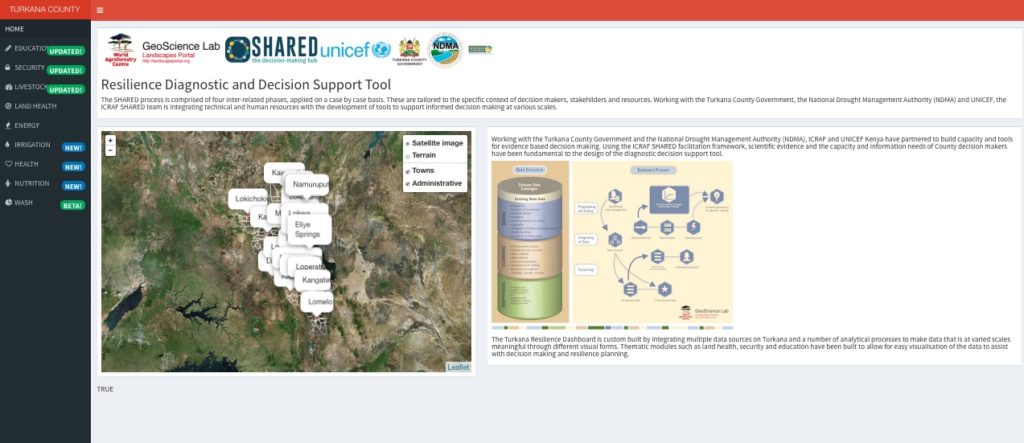

What if governments and parliamentarians had a way of knowing where their citizens needed what exactly, what condition the land was in and where to put their money most efficiently to most effectively address multiple issues simultaneously? Spatial scientists at the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) are supporting the county government of Turkana, Kenya in doing exactly that.

What if governments and parliamentarians had a way of knowing where their citizens needed what exactly, what condition the land was in and where to put their money most efficiently to most effectively address multiple issues simultaneously? Spatial scientists at the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) are supporting the county government of Turkana, Kenya in doing exactly that.

But let’s start at the beginning. In 2012, ICRAF launched the Landscape Portal, an interactive open-source website to allow users to get easy access to big data sets and select data to create maps. These big data sets were collected under the Sentinel Landscapes project of the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA).

ICRAF researchers are constantly striving to make their research data accessible and valuable to decision-makers, whether in communities or at national and global levels. This is how the idea of SHARED, short for Stakeholder Approach to Risk Informed and Evidence Based Decision Making, emerged.

SHARED operates in Kenya through a partnership between the Turkana County Government, the National Drought Management Authority (NDMA), UNICEF Kenya and ICRAF.

In 2010, the new Kenyan constitution devolved power to county governments and each county developed a County Integrated Development Plan (CIDP). The Turkana Government approached ICRAF and UNICEF and asked them for help in designing tools for planning and budgeting in order to enhance people’s resilience and reduce the incidence of emergencies. Funding from USAID made the Turkana SHARED project possible.

Setting SHARED up

At first, it was necessary to bring together all of the existing data from local and national sources, which came in different forms such as handwritten or typewritten reports, photographs or survey results. The data had to be sorted and digitized so that they then could be visualized spatially.

UNICEF Kenya brought in their experience in community engagement and data management to track progress on key socioeconomic indicators including education, health, nutrition, water and sanitation. The NDMA also provided information from their regular drought monitoring of county sentinel sites.

A major component of the work was the development of a spatial dashboard to house all the data and allow decision-makers to interact with and query the data. The design of the platform took place using a collaborative process of capacity development with the Turkana County Government.

This means that key staff at the government’s Finance and Planning Unit and other county executives had to be trained, for example in three workshops.

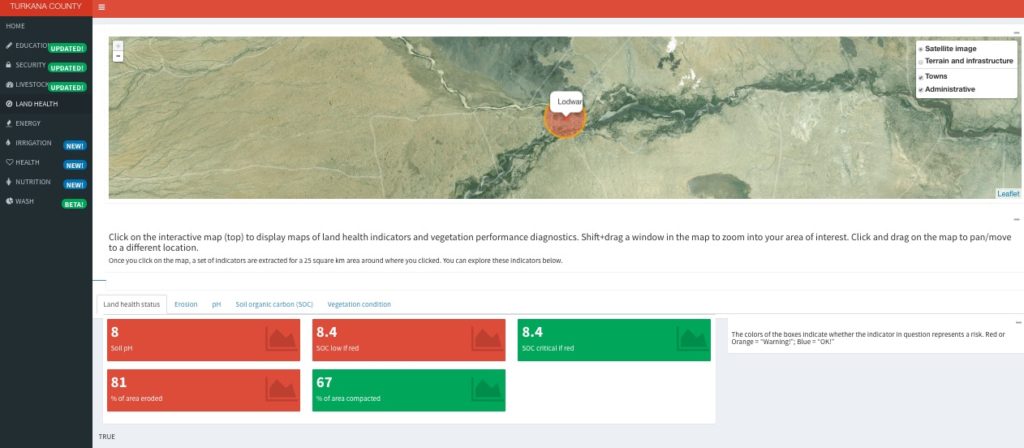

“They learned how to interpret spatial evidence to prioritize budget allocations, based on actual need,” says ICRAF’s Geoinformatics Senior Scientist, Tor-Gunnar Vagen, who has led the technical development of the spatial dashboard. “We call it the resilience diagnostic toolbox.”

In the first phase of development, the SHARED Turkana dashboard shows data for different sectors such as education, nutrition, sanitation, irrigation, security, or land health.

Vagen tells us that the tool allows the government to see for example every single school in its county with trends of teacher-student ratios and enrolment of boys and girls.

“It also shows all the security incidents in the county in a given year and where the hot spots were. This could be violence, protests or cattle rustling.”

For land health, the system is so advanced that one can click on a map, and it zooms into the location and runs different types of analyses. The map is complemented by colored boxes – like a traffic light – with red indicating a risk in that zone such as high pH, low carbon or high erosion (see screenshot).

For land health, the system is so advanced that one can click on a map, and it zooms into the location and runs different types of analyses. The map is complemented by colored boxes – like a traffic light – with red indicating a risk in that zone such as high pH, low carbon or high erosion (see screenshot).

Surprising results on HIV/AIDS

“This is where we have interaction with the county and how we try to support the county with science,” Vagen says and gives the example of the HIV/AIDS data.

“The map shows that the highest number of health facilities is in central Turkana, but the number of children with HIV/AIDS there is quite low. In the western part of the county, however, close the border with Sudan where a lot of refugees are coming through, the HIV prevalence is very high.”

So you can look at where children with HIV/AIDS get actual care in Turkana and this is not where the prevalence is high. With better data, the government and key development partners such as UNICEF can better target their interventions.”

“In Kenya almost 8 out of 10 children are subjected to deprivation in at least one of the key pillars of child well-being such as access to water, good nutrition, education, health or access to social services,” says Ousmane Niang, Chief of Social Policy of UNICEF Kenya.

“For the government and its partners in Turkana County, it is absolutely important to easily access real-time data and evidence for informed decision- making. Therefore SHARED will be a milestone in supporting the county in planning, budgeting and strengthening service delivery,” he adds.

“Partnerships and collaborations such as SHARED are the key to delivering impactful results for adolescent, children and youth.”

Taking SHARED to the next level

A joint proposal for the second phase of work is currently under review at USAID. “The idea is that we will advance the capacity to interpret and manage in the county,” says Vagen.

“In the future, it will be the county’s data, managed in their knowledge management center so that the platform can be updated, interpreted, and evidence can be shared to support decisions.”

The SHARED team would like the platform to eventually act as an early warning system for hazards and to track epidemics. In order to function like that, it will need to have an SMS-based reporting system that will more rapidly connect community experiences with county government decisions. When it is finalized, the dashboard will deliver data in real time and be able to update itself.

|

Posted by

FTA communications |

Authors: Ni’matul Khasanah, Sri Dewi Jayanti Biahimo, Chandra Irawadi Wijaya, Elissa Dwiyanti and Atiek Widayati

Communities that reside around conservation areas, such as nature reserves, often rely on the natural resources in the vicinity for their livelihoods, while ignoring aspects of environmental conservation. However, environmental conservation is needed to address community pressure, overexploitation of the resources, prevent further environmental damage and ensure that these resources are utilized sustainably. Environmental conservation efforts often trigger conflict between communities and the conservation management agency. Communities tend to consider environmental conservation efforts as a threat to their sources of livelihood. Therefore, efforts to conserve natural resources should be carefully formulated and include livelihood aspects discussed and identified in participation with the local community involved. Tangale Nature Reserve is located in Tibawa Sub-district, Gorontalo District, Gorontalo Province, Indonesia. It covers approximately 113 ha and is primarily a reserve for flora (250 species) and fauna conservation. However, encroachment on the reserve is unavoidable and causes serious degradation. Therefore, through the environmental component of the Agroforestry and Forestry (AgFor) Sulawesi Project, we have identified the need for environmental conservation efforts not only in the reserve, but also in the vicinity of the reserve, taking into account the livelihoods of the communities living in the area. AgFor Sulawesi is a five-year project that is working to address rural development challenges in Sulawesi by enhancing livelihoods and enterprises, improving governance and strengthening sustainable environmental management. The environmental conservation efforts in the vicinity of Tangale Nature Reserve, covering a cluster of villages (Labanu, Mootilango, Iloponu, and Buhu), have been formulated into a Livelihood and Conservation Strategy (LCS). The aim of the strategy is to improve community livelihoods through environmental conservation principles leading to sustainable management of natural resources. This strategy will be used as a guideline for developing agreements between the government and local communities or multi stakeholder agreements and subsequent action plans for implementation.

Publlished 2016 by World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) Southeast Asia Regional Program

Bogor, Indonesia

Volume: AgFor Livelihood and Conservation Strategy – 03

|

Posted by

FTA communications |

Smallholder systems are complex mosaics, integrating diverse land uses from forestry to agriculture.

Yet policies often draw a sharp dichotomy across landscapes – forestry on one side, agriculture on the other. The resulting mismatch between policy and actual behavior can have unintended consequences for the environment and livelihoods, or mean that opportunities are missed to better support smallholders.

A new project under the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry, a collaboration of CIFOR, ICRAF and Tree Aid – and supported by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) – is attempting to alleviate this discrepancy by increasing understanding of the real, ground-level integrated management systems of smallholders and facilitating dialogue between smallholders, policy makers and development practitioners.

“We are targeting the poorest smallholders and women living in mosaic landscapes that combine forestry and farm land uses in Burkina Faso and Ghana. Our research will focus on developing strategies to support adaptive processes important to households in these landscapes,” said Peter Cronkleton, CIFOR Senior Scientist and director of the project.

Smallholders living in mosaic landscapes depend on diverse environmental services and management behavior to provide food security, income and energy. They also produce large quantities of forest products that are crucial to rural populations, especially the poor and households vulnerable to climatic shocks. However, government policies that focus on specific sectors often target competing goals such as conservation or intensified production, introducing distortions or constraints that negatively impact smallholder livelihoods.

“Because conventional policy approaches do not take into account the diversity of land use and integrated production practiced by smallholders, the adaptive nature of these systems for providing resilience to rural livelihoods is underappreciated and these systems’ crucial importance for the rural poor – especially women – is missed,” Cronkleton said.

The West Africa Forest Farm Interface Project (WAFFI) project, supported by IFAD’s Agricultural Research for Development Program, will evaluate how such systems in Burkina Faso and Ghana offer livelihood options for rural people, and identify science-based strategies to strengthen the ability of those systems to supply income and secure food sources.

Cronkleton said, “The goal is to equip policy makers and practitioners with the evidence-base and practical knowledge needed to support smallholder livelihoods strategies and natural resource management systems – adapted to local mosaic landscapes.”

Property rights and access to natural resources are key issues for many smallholders, especially where state ownership overlaps with customary rights, as in Burkina Faso and Ghana. For example, women’s access to resources often depends on customary tree tenure systems that are poorly accommodated under formal property regimes. Without clear authority over important resources, the rural poor struggle to contest infringement on their land and customary rights.

And this is where informed policy becomes key.

“By facilitating greater engagement between farmers, policy makers and practitioners, the project will empower women and the rural poor to sustainably manage the forest-farm interface to improve their livelihoods and incomes,” Cronkleton said.

The project, which started in 2016 and extends to 2018, combines approaches from the biophysical and social sciences with participatory efforts to address the needs of targeted smallholders. Focusing on two multi-village sites in Burkina Faso and Ghana, the WAFFI project recognizes that landscapes that integrate cropland, forests and livestock require integrated institutions and policies.

The project will contribute to and be informed by CIFOR’s, ICRAF’s and Tree Aid’s current and previous work with smallholders in forests and on farms in West Africa, and fruitful collaborations with partners like IFAD. CIFOR is at the forefront of approaches that consider inclusive, mosaic landscapes, and the project is a component of the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry, allowing for scaling up to consider the contribution of trees and forests to smallholder livelihoods.

“Thanks to this collaboration with IFAD, we expect that evidence generated by this research will contribute to strategies, approaches and actions that take into account the voices of the poor and marginalized to support the livelihoods of smallholders managing the forest-farm interface for improved income, food security and equitable benefits,” Cronkleton said.

For more information about this initiative, please contact CIFOR team leaders and focal points Peter Cronkleton (p.cronkleton@cgiar.org) and Mathurin Zida (m.zida@cgiar.org).

|

Posted by

FTA communications |

Recent studies have highlighted the importance of trees and agroforestry in climate change adaptation and mitigation. This paper analyzes how farmers, members of their households, and community leaders in the Wahig–Inabanga watershed, Bohol province in the Philippines perceive of climate change, and define and value the roles of trees in coping with climate risks. Focus group discussions revealed that farmers and community leaders had observed changes in rainfall and temperature over the years. They also had positive perceptions of tree roles in coping with climate change, with most timber tree species valued for regulating functions, while non-timber trees were valued as sources of food and income. Statistical analysis of the household survey results was done through linear probability models for both determinants of farmers’ perceived changes in climate, and perceived importance of tree roles in coping with climate risks. Perceiving of changes in rainfall was more likely among farmers who had access to electricity, had access to water for irrigation, and derived climate information from government agencies and mass media, and less likely among farmers who were members of farmers’ organizations. On the other hand, perceiving of an increase in temperature was more likely among famers who were members of women’s organizations and had more off/ non-farm sources of income, and less likely among those who derived climate information from government agencies. Meanwhile, marginal effects of the regression on perceived importance of trees in coping with climate change revealed positively significant relationships with the following predictor variables: access to electricity, number of off/non-farm sources of income, having trees planted by household members, observed increase in temperature and decline in yield, and sourcing climate information from government agencies. In contrast, a negatively significant relationship was observed between recognition of the importance of tree roles, and level of education, and deriving income from tree products. In promoting tree-based adaptation, we recommend improving access to necessary inputs and resources, exploring the potentials of farmer-to-farmer extension, using participatory approaches to generate farmer-led solutions based on their experiences of climate change, and initiating government-led extension to farmers backed by nongovernment partners.

Authors:

Published at Agroforestry Systems, June 2016

|

Posted by

FTA communications |

Presentation by Meine van Noordwijk at ICRAF side event on ecological rainfall infrastructure at the Paris COP21

|

Posted by

FTA communications |

The World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), the University of Copenhagen and partners have developed a new version of vegetationmap4africa (www.vegetationmap4africa.org) map (ver. 2.0). The map with help identify species easily in the field and at the same time help scientists gain a deeper understanding of their natural environment.

|

Posted by

FTA |

By Sander Van de Moortel, originally posted at ICRAF’s Agroforestry World Blog

Visitors from all over Indonesia flock to small villages in Southeast Sulawesi that have found ways to increase their profits while reducing environmental impact. The villagers are keen to share their knowledge.

The occupants of the car brace themselves as it suddenly swerves left, off the safe asphalt and onto a muddy stretch of pits and holes, a treacherous landslide and low-hanging branches that thrash the windscreen. In the makeshift motorcade behind them are government officials, members of the press, the AgFor team, and a delegation of farmers and a scientist from FORCLIME, a German-sponsored sustainable development project in Indonesia. Hailing all the way from Kapuas Hulu, a remote area of Indonesia’s Kalimantan island, they have come to learn from AgFor’s successes on farms in Southeast Sulawesi province.

The cars halt in Lawonua, a small village where the visitors are welcomed by Mr Mustakim, a cheerful rotund man in his forties. Mr Mustakim is the leader of the local farmer group that has agreed to be part of AgFor, and his cacao and pepper farm is one of the project’s demo plots. In fact, as visitors who enter through the gate overgrown with passion fruit will soon discover, Mr Mustakim’s cacao and pepper have the company of a number of other crops, including oranges, banana, coconut, papaya, and rubber. Near the gates, a dragon fruit cactus is slowly making its way up along a tree trunk.

The attendants take place under a tarpaulin shelter on the farm’s surprisingly cool north side. Mr Parinringi, the district’s vice-bupati (vice-mayor) grabs the microphone to shower praise on the AgFor project. “I am extremely pleased with the positive impact in our district,” he said, adding that he deplored that the project’s five-year term was coming to an end: “Ideally, I’d like to see the project continue for several more years.”

Mr Akbar, who heads the local extension office, also highlighted that they established an information centre which houses a small library of books about agricultural techniques and processing methods.

Vice-bupati Parinringi congratulates Mr Mustakim in Lawonua village and is very open for more projects under AgFor

Agroforestry techniques became common in Southeast Sulawesi about 20 years ago when land-use intensified with the immigration of farmers from South Sulawesi, Java and Bali. After the forest conversion, the fertile forest soil allowed for high yields. But limited knowledge and poor practices led to substantially lower yields, which forced farmers to clear ever more original forest for their crops.

“What we’re doing here is essentially just starting the engine,” explains Mr Mahrizal, who coordinates the Southeast Sulawesi leg of the AgFor project. “The hardest work is establishing the demo plots so that we have a tangible proof of concept. Once the news spreads and other farmers see the trials for themselves, agricultural practices Sulawesi will change swiftly.”

Hubertus Tengkirang from GIZ Forclime inspecting a cacao-pepper agroforest at Onembute village

And the new techniques did bring about change. Mr Abdul Kadir, who is part of the farmer group from Onembute village, beams as he announces that his family managed to send their child to university to obtain a master’s degree. “I would have never had the means if I hadn’t joined this group.” The visiting delegation from Kalimantan took notice.

“It’s one thing to learn about new techniques,” said FORCLIME facilitator Mr Petrus, “but many farmers aren’t keen to try on something so radically new. For them and for us, seeing is believing.” It is one of the reasons why the AgFor project arranges these so-called cross-visits. Mr Petrus is himself from a Kalimantan farmer family, but was lucky to study agriculture in Malaysia. Him and his colleagues now help to collect and spread information to the farmer groups back home.

Mr Agustang and Ms Ramlah in front of their colourful house and cacao-pepper farm

The visitors curiously inspect the farm’s equipment: the extensive tree nursery that provides high-quality seedlings for the farmer group, the propagator where cuttings from plus-trees (superior specimens) of valuable species are rooting, and the compost heap that produces small quantities of organic fertilizer for the farm.

The villagers are as keen to share their knowledge and experience with the visitors. Questions are fired back and forth as Mr Mustakim demonstrates his grafting and pruning skills on an unsuspecting cacao tree. Mr Iswanto, who presides the local extension agency, discusses ways to preserve or process surpluses of durian in response to its plummeting price when mid-season supply exceeds demand, and to prevent pod borers from ruining the cacao harvest by not intercropping with rambutan.

Mr Petrus collecting valuable information for Kapuas Hulu farmers in Kalimantan

The delegation visits three more villages in other districts of Southeast Sulawesi. The villages are ever more remote, the roads ever more inaccessible. Despite the dry weather conditions, a small truck has driven into the ditch, requiring the visitors to find a different route into town.

Yet wherever they went, local government, ranging from village heads to district heads and including all involved agencies, unanimously agreed that AgFor has brought nothing but good. “I’m very proud of what we have achieved in my village,” says Mr Lukman, who is the leader of Aunupe village in South Konawe district. “With five more years of AgFor, I think we will be able to stand on our own feet even better than now,” he adds hopefully.

Ms Sumiasi spreading out drying cacao seeds

The villagers, too, are happy with the current results. Seated on the floor and snacking on some peanuts, Ms Sri Utami says the spirit in the village has improved considerably since the project’s start. She herself has taken part in a training to build and manage nurseries and propagators. “People from all over the region are coming to visit and see our work, and visits like today’s open the windows of our souls.”

On the way out, Mr Mahrizal enthusiastically taps on the window pane. “Look, another farmer group has copied the nursery idea!” Indeed, when good ideas take root, they grow vigorously.

A colourful goodbye

Agroforestry and Forestry (AgFor) in Sulawesi: Linking Knowledge to Action (AgFor) is funded 2012–2016 by the Government of Canada through Global Affairs Canada and the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry. After establishing itself in South and Southeast Sulawesi, operations in Gorontalo Province began in early 2014. In its implementation, AgFor works closely with the local government and is led by the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), with support from its partners, the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) and local organisations in each province: Balang and Universitas Hasanuddin in South Sulawesi; Operasi Wallacea Terpadu (OWT), Komunitas Teras and Yascita in Southeast Sulawesi, Japesda and Forum Komunitas Hijau (FKH) in Gorontalo. The project seeks to make agroforestry a truly sustainable practice, by enhancing existing practices, inspiring innovation, disseminating information, encouraging enabling policy, and by ensuring that the reward is worth the investment risk.

|

Posted by

FTA |

La Ode Ali Said showcasing Southeast Sulawesi forest honey at the Pekan Panen Raya Nusantara 2015 exhibition in Jakarta

Concluding five years of AgFor, a multilateral project aimed at promoting agroforestry practices in Indonesia’s exotic Sulawesi region, participating farmers are now starting enterprises to process and market their products beyond their own village.

Funded by the Government of Canada and established by ICRAF The World Agroforestry Centre in April 2001, the AgFor project has been actively promoting agroforestry technologies in Sulawesi, an island in eastern Indonesia. Generally deemed more environmentally sustainable than monoculture, agroforestry is more suitable to farmers’ conditions providing multiple products and lower risks. AgFor also helps farmers to bring their products to market and sell them at a premium, as a reward for their investment in sustainable management.

While the high-value commodities such as black pepper and cacao are readily bought by traders and global concerns, some products are not marketed in the mainstream, such as sagu flour, palm sugar, forest honey and compost. At the behest of the farmers in the participating farmer groups, the AgFor team helped out with business plans, packaging, labelling and marketing.

Meet the honey hunters of Uluiwoi, a subdistrict of East Kolaka who traditionally scout the forests for honeycombs produced by the wild honeybee or Apis dorsata. When they find such a golden blob, sometimes hanging as high as 40 m above the ground off a tree branch, the daredevil leader or sopir (driver) clambers up the trees, smokes out the bees, and cuts down the honeycomb. Back on the ground, the pasoema, as the honey hunters are called in local Kolaka language, squeeze out the honey along with eggs and pupae into used water bottles. The resulting honey has all kinds of hygiene and quality problems and a 250 ml bottle sells for no more than USD 1.2. A meagre return on investment to say the least, knowing that groups may spend up to a week in the forest and some climbers never return.

“We thought they could do better,” says AgFor’s marketing facilitator La Ode Ali Said. “We identified a more sustainable and hygienic method which involved carefully cutting the honey bag to slowly drain the golden liquid. It is then filtered through a fine mesh, resulting in a very pure honey.”

Bottles of premium forest honey

The AgFor team, for this component reinforced by CIFOR, Komunitas Teras and Yascita, invited a marketing expert from Hasanuddin University in Makassar to train the villagers in marketing and entrepreneurship. From the training, a cooperative of honey hunters from four villages was born, which buys drained honey from the pasoema. “The honey is now sold in more hygienic packaging with attractive labelling,” says Mahrizal, provincial coordinator of AgFor’s Southeast Sulawesi activities. “The reward is a higher price for the product.”

A 250 ml bottle of the cooperative’s honey now sells for IDR 50 000 (USD 5) in the provincial capital of Kendari. “It’s such an enormous success,” says Kusman who heads the cooperative. “Our entire production of 650 kg sold out well before the start of the next season.”

The AgFor team are now looking to make the product even more attractive by improving the quality. “If we manage to lower the water content below the current 20%, we may one day be able to achieve what our colleagues have done with the Kanoppi project in Sumbawa,” says Mahrizal. Sumbawa honey currently trades for three to four times the price.

Another AgFor project brought organic palm sugar from East Kolaka to the market

In March and July 2016, AgFor and the local government’s trade and cooperative agency held a series of marketing and entrepreneurship workshops for six farmer groups. The training included basic marketing theory followed by a creative component in which the farmers were encouraged to draw up a fictive business plan for products from their farms. The Mepokoaso farmer group from Tobimaeta village in Kendari district saw an opportunity for marketing its surplus of sagu.

Sagu, a white substance procured from the stems of the sagu palm, is an important commodity in parts of Sulawesi. “It is normally consumed when it is still wet, but when dried it can be sold as flour for use in pastries, drinks, soups, and for other cooking purposes,” explains La Ode Ali Said.

The farmers traditionally sun-drying the wet sagu on tarpaulin which was curled up at the edges to keep out the dust. AgFor marketing facilitators helped farmers created improved processing and packaging techniques and an attractive label. The sagu is now sold beyond the village’s direct surroundings in carefully sealed plastic bags of 500 g and 1 kg. In the future, when production is up and more stable, the label will feature a complete nutritional value chart, which will allow it to be sold in supermarkets around the province and beyond.

Labelled package of Sagu flour

Supported by Operasi Wallacea Terpadu (OWT), AgFor held several workshops on the production of organic fertilizer. These quickly started to bear fruit, with many farmers in Potuho Jaya village in South Konawe district producing their own compost from organic waste, stems, leaves, and goat or cow manure. “Initially we only sold our compost in and around the village,” says Mr Jingun who leads the Potuho Jaya farming group, “but as demand grew from Kendari and several of the surrounding dragonfruit and ginger-producing villages, we saw an opportunity to expand.”

Acknowledging the benefits of organic over chemical fertilizer, village heads and ginger processing companies alike encouraged farmers to purchase from the Potuho Jaya compost producers. The AgFor project team helped out with the labelling, and provided a machine that took care of the packaging and sealing. The village now sells in a wider area, producing up to 2–3 tonnes of finely ground compost per production cycle. Selling at IDR 50 000 per bag of 30 kg, the village now runs a profit of 1 million Rupiah (USD 100) per batch of 1.5 tonnes.

Kusuma, head of OWT, helps farmers of Potuho Jaya sealing a bag of their very own organic fertilizer

Agroforestry and Forestry (AgFor) in Sulawesi: Linking Knowledge to Action (AgFor) is funded 2012–2016 by the Government of Canada through Global Affairs Canada and the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry. After establishing itself in South and Southeast Sulawesi, operations in Gorontalo Province began in early 2014. In its implementation, AgFor works closely with the local government and is led by the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), with support from its partners, the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) and local organisations in each province: Balang and Universitas Hasanuddin in South Sulawesi; Operasi Wallacea Terpadu (OWT), Komunitas Teras and Yascita in Southeast Sulawesi, Japesda and Forum Komunitas Hijau (FKH) in Gorontalo. The project seeks to make agroforestry a truly sustainable practice, by enhancing existing practices, inspiring innovation, disseminating information, encouraging enabling policy, and by ensuring that the reward is worth the investment risk.

|

Posted by

FTA |

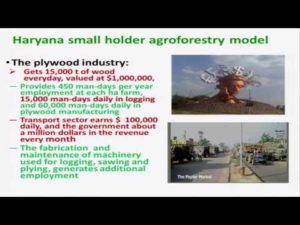

The approval of India’s agroforestry policy in 2014 has been a first step in a global process supported by the FAO and the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF). This year, for the first time, the Indian government has approved a budget for agroforestry of US$ 150 million. V.P. Singh, ICRAF’s Senior adviser for policy and impact has been the motor of the agroforestry success story in India. He is currently drafting a Working Paper that reflects on “Developing and Delivering Policy: An Experiential Process Learning in Developing the National Agroforestry Policy of India”. His work forms part of the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry. We spoke to V.P. Singh at the sidelines of ICRAF’s Science Week in Nairobi 5-9 September 2016.

What are the biggest problems for agroforestry and for farmers who practice agroforestry in India?

Agroforestry or “Krishivaniki” had been practiced on the Indian subcontinent for a long time, , but it the business of the farmers alone. Politically, it was housed neither in agriculture nor in forestry, consequently as it lacked a supporting regulatory framework the farmers could not take out loans or insurance policies for agroforestry practices.

And, of course, extension services were not trained or equipped to support farmers who practice agroforestry on their land. There was no capacity building as needed.

But the biggest problem by far were the restrictions to tree-cutting and transit of timber that are enacted and enforced by the Ministry of Environment and Forests and Climate Change. Under these rules enacted to help protect forests, farmers were required to undertake a cumbersome process to obtain permits to cut trees even if they planted them, and even in areas absent of threats because there were no forests.

What was originally well-intentioned, to counter deforestation, became a major impediment for farmers who wanted to plant trees for timber values, as they were not allowed to fell them for any purpose.

How did ICRAF tackle these issues?

Around 2009 we started talking to the government and flagged that practicing agroforestry posed a problem. With support from the Indian government, we organized two national consultations one in 2011 and one in 2012. Based on these meetings, we were able to develop a rationale for agroforestry to be taken up in the form of a national policy for agroforestry. A policy is a living document, a wish list of the government, good at large for everyone.

After that, we started having consultations nearly every month. The main challenge was to engage different federal and state level ministries, and other agencies without their fighting over their competencies and justifications, pro or against having a policy . So we had to dialogue with them one at a time to get their input.

In those monthly meetings we gathered feedback first from the union government, then from the states, industry, financial institutions, international organizations, farmer groups and last but not the least from the civil society community. You get everyone’s concerns but you avoid them fighting face to face. And it worked, it worked very well.

How did you make the government see that they needed an agroforestry policy?

In every meeting I gave a presentation on what are the benefits of agroforestry, many endorsed by hard numbers. I reminded them that 62 percent of India’s timber requirements are met from the farms, US$ 24-30 billion in monetary terms. And there are also crops grown on the farms, which is additional. I made them see this as an economic issue. This is more than a 40-billion-dollar economy, and mostly from smallholder farms.

If the timber isn’t produced on farms, it has to be imported: 20 percent of the timber used in India is imported. We are talking about US$ 8 to 10 billion every year.

I also reinforced the notion that agroforestry can be practiced at a very small scale, by the marginalized smallholder, and at a very big scale, as well as in various designs and combinations in all ecological and socio-economic settings in the country. I presented evidence in the form of case profiles.

And, after a steady information sharing process in nine meetings over eight months, everyone agreed.

Everyone agreed, but where is the agroforestry policy?

In 2013, we formed an agroforestry policy drafting committee that set out to come up with a first draft. Feedback was collected from everyone concerned through electronic media, in hardcopy, even over the telephone. This feedback was incorporated into a second draft and when that was ready, we invited 100 stakeholders to a meeting to finalize.

We sat in a big room for 12 hours until everyone agreed on the final version, which was then sent to the cabinet and after its approval from the cabinet India’s first Agroforestry Policy was laid to both the houses of the parliament in 2014. We made sure to include deliverables and pathways to these deliverables. So the agroforestry policy is the only government policy in India that actually has clear deliverables and pathways.

So ICRAF facilitated the process and that was it?

We were able to very significantly influence the actions in the government and we are still involved because the government created an inter-ministerial committee to oversee the implementation of the policy, in which ICRAF is a permanent invitee member. Right now, I hold this position. ICRAF is also an official implementing partner and can support states in their development projects. We are also involved in capacity building on state level. We were able to successfully promote the cause of agroforestry because we didn’t impose anything on the government; it was a completely consultative process.

Two years have gone by. Are you satisfied with the progress in policy implementation?

Absolutely. This year, the government has for the first time approved an Agroforestry Mission, and budgeted US$ 150 million nationally to boost agroforestry. This money is 60 % of the total fund as 40% additional funds will be made leveraged from the state finances, and that will make about US $ 210 million. The money will specifically go to those states that follow the policy’s guidance to relax the tree felling and transit regulations for selected tree species in the respective states. We suggested that they start by freeing at least 20 species from these regulations. This made it easier for them to accept the policy.

Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana and Chhattisgarh have already exempted between 20-84 species from the felling and transit restriction.

Currently, each state can come up with a proposal of how they will use the “Mission money” for agroforestry in order to benefit from it. Which agroforestry system do they want to scale up? Who will be the main beneficiaries? And the inter-ministerial committee will scrutinize the proposals and decide where to put the money.

Thus, it will automatically benefit smallholders because smallholders and marginal holders make up about 85 percent of all farmers in India.

But the greatest impact in my view is the fact that agroforestry is now a distinctly recognized pathway in agriculture. New investments are made and institutions are upgraded. For example we now have a Central Agroforestry Research Institute with proper staff positions and budgets.

The policy drives the government’s command to have trees on every farm, and the progress we have already made in agroforestry would not have been possible without the policy.

|

Posted by

FTA |

Elok Mulyoutami is an anthropologist and sociologist with the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), working on the Agroforestry and Forestry in Sulawesi: Linking Knowledge with Action (AgFor) project in Sulawesi, Indonesia. AgFor Sulawesi is a project that has been running for five years and involves local communities, civil society groups, conservation organizations and universities to improve farmers’ incomes through agroforestry and natural resource management systems. We asked Elok Mulyoutami about her work and professional background.

Elok, in your own words, what is this project about?

AgFor is a Research in Development project which means that it seeks to address a development issue through research and that we must ensure that the results of our research are used for development processes. AgFor is a collaboration between ICRAF, the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), universities and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

There are three interlinked components: Livelihoods, Governance, and Environment. The Livelihoods and Environment components are led by two different ICRAF teams, the Governance theme is managed by CIFOR.

All project activities are designed and implemented to be gender-inclusive and project data and results should be disaggregated by gender.

Can you tell us a bit more about the different components of the project?

The project has three components

(1) Improve sustainable and gender-equitable use of agroforestry and forestry products for livelihoods by poor women and men,

(2) Increase equitable involvement of women and men in participatory governance of land use and natural resources at sub-district and district levels,

(3) Improve integrated management of landscapes and ecosystems (environment) by local stakeholders through enhancing their capacity.

Under the Livelihoods theme, we want to improve the sustainable and gender-equitable use of agroforestry products, and to increase women’s participation in governance issues related to forestry.

All three components are designed to create synergies and support each other, and the ICRAF and CIFOR teams work closely together. CIFOR’s work relates to local institutions and NGOs at the three sites in South Sulawesi, South East Sulawesi, Gorontalo provinces.

ICRAF is responsible for designing ecosystem services schemes and livelihood enhancement activities, we have people based there and also collaborate with local NGOs.

What is your role in AgFor?

My responsibility in this project is to make sure that the project implementation is still on track in being gender inclusive and that the data are in fact disaggregated.

The first thing we do is to identify a baseline related to gender issues e.g. income, gender relation, and different knowledge of men and women in each community that we are working with.

Next, we trained everyone involved in the projects, ICRAF staff working in the field, and all implementing partners on the ground in how to conduct gender sensitive projects.

The training program is meant to improve people’s skills in integrating gender in cross-sector programs and to make researchers and implementers understand how gender-sensitive indicators can be used as tools for measuring the results of AgFor. In this, we have to consider the Gender Equality policy of Global Affairs Canada (previously CIDA). Of course, we regularly monitor our progress.

What were the main project activities?

The project target is to reach a women’s participation of at least 50 percent for the outcomes and outputs.

We approach the communities and encourage both men and women farmers to form farmers groups. In these groups, we train the farmers to develop a good nursery, how to produce a high-quality seedling, to deal with the market, pest and disease control. Basically, how to improve their knowledge of everything related to improving the productivity of their garden.

Our local teams, based in every province, play a very important role as facilitators. These teams come mostly from ICRAF and some local NGOs.

With regards to the farmers groups, the communities can decide if they want to have separate groups for women and men or if they want to mix. We observed the progress of the groups and found that the success is not easy to predict. Sometimes mixed groups perform better than the ones separated by gender. The performance depends very much of the location, which, of course, expresses itself in a specific culture and local tradition.

Then, of course we promoted the farmers groups and found a farmer champion in some villages to help us get the message out and encourage participation in the wider communities in each villages. We helped develop 139 farmers groups with more than 2881 farmers as members, 35 percent of them are women, and nearly 10 percent of the women involved are quite vocal in the villages.

How do you explain the project’s gender aspect to the local people?

We try to encourage both men and women to attend the farmers meetings, but we leave it to them to decide if the husband or wife comes alone or if they both attend. We encourage them to also work together in the field, so if one of them has learned something new in the training he or she should communicate it to the other.

It’s easy for the project staff to bond with the local communities because we have offices near the villages where we do our research. Female researchers are available in case we want to gather information on sensitive issues, about which a woman might not talk to a man.

We also have co-facilitators who come from the local communities and speak the same language. They can help in communicating, as the language can be a problem for us in certain locations. And it is important that we don’t force them to participate, but rather encourage them.

How has this project emerged from previous research?

Previously we had projects related to livelihoods, to the environment or to governance, but they were maintained separately. In AgFor, we have integrated the three areas and interlinked them. We learned from previous research that it makes sense to bring them together.

More precisely, in 2007 and 2009 the Government of Canada supported ICRAF in implementing the Nurseries of Excellence (NOEL) Project in Aceh, with the goal of rebuilding agricultural infrastructure after the 2004 Tsunami. The NOEL project was very successful, exceeding its targets.

Therefore, the Canadian government asked ICRAF to develop a project for Sulawesi that would build on lessons learned in the NOEL project.

South Sulawesi, Southeast Sulawesi and Gorontalo were selected as the AgFor project sites to strengthen and diversify farm livelihood systems of rural communities where people where surviving at or below the poverty line. The project aimed to protect communities’ natural capital and Sulawesi’s unique biodiversity.

The projects before AgFor had gender inclusive approaches and disaggregated achievements and data, but unlike AgFor they had no explicit gender target and did not put as much emphasis on gender outcomes.

You’ve worked with indigenous communities and sensitive issues. Did you encounter challenges related to cross-cultural research during this project? If so, how have you dealt with them?

AgFor works with both indigenous and migrant communities. We follow the cultural norms of each community, adjusting our approach accordingly.

One of the first things we do when entering a community is to stress the need to have a gender equitable approach. Group discussions are used to identify the gender roles and knowledge regarding agriculture production, livelihoods and natural resource management.

That way, the communities can identify for themselves that each gender holds crucial knowledge and skills. They can understand the importance of a gender-equitable approach.

What can this project achieve?

After five years, we can say that AgFor has contributed to a more equitable use of agroforestry as well as agroforestry products. Our data supports that. At farm-level, the participation of women has increased. This means that for the Livelihoods component, the outcome in terms of gender research is positive. For the areas of Governance and Environment it is much more difficult to change things quickly, which is why the representation of women is still rather weak in these areas.

What is your professional background?

I’m an anthropologist and also have Master’s degree in rural sociology. I have been working with ICRAF since 2003. In the beginning, my research was related to local knowledge, so I gathered information from the villages on biophysical issues.

I became interested in gender issues and when gender became more important in ICRAF, people started saying: You could be good as a gender specialist. So I started to learn more about it. This must have been around 2010.

Before ICRAF, I had worked for local NGOs that were involved in research in social sciences. That was in Bandung, we call it Akatiga, center of social analysis.

When I came to ICRAF, I learned more about the biophysics aspect. The fact that I am able to combine all those disciplines gives me so many advantages.

Given that this is the gender newsletter of the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry, we would like to ask you: if you were a tree, which tree would you be, and why?

I would definitely be a coconut tree, because it has multiple uses. Coconut products are cheaper compared to other tree crops, but every part of the tree can be used.

Further reading:

Impact story: Sulawesi provinces promise to stick with agroforestry

Nipa-Nipa reserve saved by multilateral alliance of government, farmers and NGOs

Kolaka Timur District moves to adopt agroforestry

Changing mindsets and landscapes in Sulawesi one district at a time

|

Posted by

FTA |

By Kerstin Reisdorf

The World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) has a lot to offer to help developing countries reach the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and should make agroforestry exemplary for a nexus of different land use-issues. This was one of the main messages of ICRAF’s Science Week 2016. But there are challenges, participants agreed, such as fostering cross-sectoral approaches with the right science. Director General Tony Simons expressed satisfaction that agroforestry was gaining more recognition, e.g. the French agriculture ministry just released an agroforestry development plan. The 120 scientists also debated the “refreshing” of ICRAF’s strategy in the light of the SDGs and the climate agenda, before it will be handed over to the Board in November. Plenaries also dealt with hypotheses to guide ICRAF’s science, and land restoration, among others. As is customary, field trips were organized to show the work of ICRAF partners.

Silos no more

“Integration is at the core of what needs to happen to make the SDGs work,” said Peter Minang, Leader, Environmental Services research unit Domain at ICRAF. Division of land uses into different sectors, as it is today, has to be overcome to drive the nexus of food, water, energy plus the factor income. He deplored that in governance “there is no bonus for agriculture and forestry working together” when cross-sectoral action was key to really make progress on the way to reaching the SDGs and to address trade-offs and create synergies at the landscape level.

“Integration is at the core of what needs to happen to make the SDGs work,” said Peter Minang, Leader, Environmental Services research unit Domain at ICRAF. Division of land uses into different sectors, as it is today, has to be overcome to drive the nexus of food, water, energy plus the factor income. He deplored that in governance “there is no bonus for agriculture and forestry working together” when cross-sectoral action was key to really make progress on the way to reaching the SDGs and to address trade-offs and create synergies at the landscape level.

Scientists need to ask questions on how agroforestry compares to other land uses and how it supports the process towards integrated action by also meeting other objectives within the landscape, Minang added. Trade-offs and conflicts between land users have to be managed so that synergies can be created. These processes need negotiation support and this is “where our work really comes in handy, as it provides the evidence that is needed.”

“We have to do a bit more work on finance,” Minang said. There are two aspects of finance to enable the nexus approach, blended finance from multiple sources, and performance-based finance. He gave the example of the pilot project DRYAD on community in Cameroon. “You put in public money as a start-up process that generates a sustainable land-use-based enterprise.” This money is tied to the recipients’ meeting their deliverables.

Insights from agroforestry

His theme of integration was echoed by guest speaker Alexander Müller, Study Lead TEEBAgriFood, hosted at UNEP. “The silo orientation of the past is not going to solve the problems of the future.” An integrated approach would help to look at the competition for natural resources everywhere. He argued for a participatory approach, bringing together scientists and the people in the landscape to identify the issues.

But the interdependency of the elements food, water, energy plus income was also relevant at the global level, e.g. biofuels have an impact on the landscape but are also closely related to global trade, he added.

Müller, who is also a Member of the German Council for Sustainable Development (RNE), sees agroforestry as “kind of a micro nexus” for the SDGs, because in agroforestry one has to deal with food, energy, water and income.

With its capacity to analyze problems and present evidence for solutions, “ICRAF has a lot to offer,” he said. “Why not use the insights gained from agroforestry to present the management of natural resources at the landscape level in an integrated way and make it part of the successful implementation of the SDGs.”

Overcoming barriers

Deputy Director General Research, Ravi Prabhu urged his colleagues to come up with “liberating hypotheses”. “We are not going to get a nexus approach unless we tackle the barriers,” he warned. The barriers could be structural, i.e. lie in the ways that societies are organized.

Deputy Director General Research, Ravi Prabhu urged his colleagues to come up with “liberating hypotheses”. “We are not going to get a nexus approach unless we tackle the barriers,” he warned. The barriers could be structural, i.e. lie in the ways that societies are organized.

To break down the barriers on the way to a nexus approach it needs a revolution—from the researchers in a context of agriculture in and for development, Prabhu said. ICRAF has to define hypotheses to address the nexus of food, water, energy plus income if it wants to be part of the solution.

Integration starts with data sharing

Valentina Robiglio, a Landscape Ecology and Climate Change Specialist in Latin America, called on her colleagues to promote intergovernmental cooperation by encouraging all units within a government to work off the same data. “That would be a start towards more integration,” she said.

Overall, the “nexus” discussion on the last day of the annual meeting was somewhat exemplary for the current discourse at ICRAF. Many other important debates took place in the sub-plenaries, and a recurring theme was—in simple terms—how does ICRAF produce relevant science?

View from outside

The donor perspective was brought into the discussion by Steve Twomlow from the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD): He urged scientists first of all to communicate their work to the users in much simpler terms.

View from the ground

Post-doctoral fellow Mary Njenga brought in the perspective from the ground by reminding the audience that rural women in Africa are in need of safe energy sources while facing a myriad of constraints; starting with the time they spend on collecting firewood, a recurring shortage of woodfuel and the health hazard from indoor cooking fumes, to name only a few.

She suggested to include bioenergy production in the CGIAR FTA, under Climate change mitigation and adaptation. “The big question is: How can we sustainably produce bioenergy in developing countries?” Njenga said. The aim would be to realize an integrated food and bioenergy production policy and practice. Her message was underpinned by a film on women in Kenya’s West Aberdares, produced by Stockholm Environment Institute.

All presentations can be found at www.slideshare.net/agroforestry

For more stories from ICRAF’s Science Week watch this space.