The Forests, Trees and Agroforestry research program (FTA) of the CGIAR has just released an extensive evaluation of its research portfolio on oil palm in Indonesia, which assesses the influence of the work on policy, practice, partnerships, and research within the sector.

While this growth has contributed considerably to the country’s income, it has also been linked to severe environmental impacts, such as increased instances of fires, deforestation and peat exploitation, resulting in carbon emissions and biodiversity loss. There are also social challenges as the industry grows and becomes more regulated, such as smallholder disenfranchisement.

In that context, FTA’s leading partner, the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), has been carrying out a number of research projects in Indonesia since 2010 to better understand Indonesia’s governance of and policy process for oil palm management; the biophysical characteristics and ecological implications of oil palm production; and the social realities of oil palm expansion.

Now, FTA’s Monitoring, Evaluation, Learning and Impact Assessment team (MELIA) has released an evaluation of that research. MELIA chose four key projects, valued at around USD7 million of investment, to represent the portfolio: Supporting Local Regulations for Sustainable Oil Palm in East Kalimantan (EK), Governing Oil Palm Landscapes for Sustainability (GOLS), Oil Palm Adaptive Landscapes (OPAL), and Engendering Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) Standards (ERS).

The evaluation assessed the project design, implementation and outcomes of those initiatives. “The objective was to assess the extent to which CIFOR’s research on palm oil has influenced policy and practice in Indonesia – and to learn from that,” said evaluation manager and CIFOR Research to Impact team leader Jean-Charles Rouge.

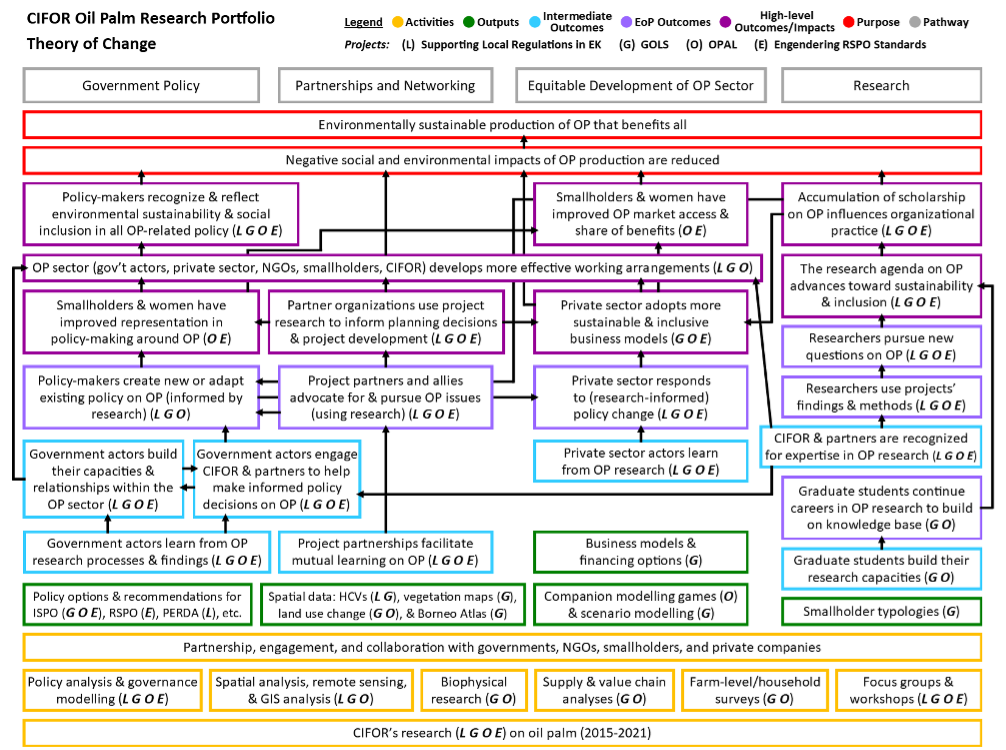

The team used a new Theory of Change (ToC) as the analytical framework for the evaluation. It combined key elements of the four projects to create a composite ToC, which sketched out the theoretical relationships and sequences of steps through which the portfolio aimed to contribute to particular outcomes and impacts. The portfolio’s ToC identifies a total of 21 outcomes at three distinct levels:

- 6 end-of-project outcomes that are reasonable to expect and observable at the time of the evaluation, and therefore are testable;

- 7 intermediate outcomes that relate to changes in knowledge, skills and relationships, and

- 8 high-level outcomes to support the causal logic from end-of-project outcomes to impacts and project purpose.

The distinction between end-of-project and high-level outcomes is made because higher-level results are expected to require more time to manifest and depend on variables beyond the influence of the project. The evaluation then tested to what extent and how outcomes were realized, using document review and interviews with relevant stakeholders (see Table 1).

The evaluation constituted a significant undertaking in terms of data collection and validation. Over 200 documents were reviewed, 89 interviews were conducted, and a total of five sense-making workshops were held to validate and solicit additional input to the report with representatives from government, NGOs, partner organizations, researchers, and FTA.

“CIFOR had already used a theory-based evaluation approach in previous evaluations of research projects,” said Rouge. “But in this evaluation, for the first time, the approach was used for a portfolio of projects, which led to a number of methodological challenges – on top of navigating in a very politically sensitive sector. The evaluation team addressed them well and ensured that all stakeholders had an opportunity to voice their views”.

Rachel Davel, one of the evaluators from the Sustainability Research Effectiveness (SRE) Program at Royal Roads University, added that “this evaluation offered us an opportunity to work with a composite theory of change to represent the intended contributions of multiple research projects. This required additional validation from researchers of the four projects to ensure the composite accurately reflected the collective research efforts and outcomes of the portfolio. We have since transferred this learning to another study to document composite theories of change to assess the FTA program.”

Rachel Claus, another member of the SRE evaluation team, noted that the value of the theory-based evaluation method was the ability of the analytical framework to make explicit and test outcomes organized around collective research contributions. “Using a theory of change framework was helpful to identify where projects were well aligned to reinforce each other and build on outcomes, and where there was scope to be more strategic, coordinated, and intentionally designed for impact,” she said.

The evaluators found that the portfolio fully contributed to the realization of 12 of the 21 outcomes and partially contributed to six of them identified in the ToC. Some notable achievements include: shaping a provincial-level regulation in East Kalimantan to include high conservation areas; government partners building new expertise in oil palm topics; ally organizations using FTA findings to hold private palm oil companies accountable to their commitments; RSPO changing international oil palm certification standards to reflect gender considerations; skilling the next generation of young researchers; and advancing oil palm research.

Six of the seven intermediate outcomes, which related to changes in knowledge, skills, and relationships, were met. While there is an indication that the outcome related to the private sector learning from research was partially realized, the lack of evidence could not fully support this claim. The report explains how private sector engagement was a shortcoming of the portfolio. As a lesson, this could be a focal area for future research on oil palm that could support cross-sector engagement and progress toward sustainability in the sector.

Five of the six end-of-project outcomes were also realized, although some of the portfolio’s higher-level outcomes are yet to be met; many of these depend on factors and processes that are beyond the direct influence of the portfolio.

The portfolio mechanisms that proved to have most influence related to new knowledge production and the scientific reputation of CIFOR and its partners. For instance, the smallholder typology developed by GOLS contributed to raising awareness about the need to focus policy to give the right assistance to the right kind of smallholders. “Numerous interview respondents appreciated the neutral, credible, and research-based information that CIFOR can offer to support constructive dialogues and collective action in a contentious sector,” the report underlines.

“Overall, FTA’s research portfolio produced knowledge on diverse aspects of oil palm sustainability and contributed to notable changes in policy, partnerships, capacity-building, and the research agenda,” said Davel. The evaluation concludes that there is potential for future oil palm production in Indonesia to take place in ways that have both enhanced social benefits and fewer negative environmental impacts – if it is well-guided by government regulation, private sector commitments and research to inform sustainable and inclusive practices. However, the report also noted that there are currently a number of barriers to realizing this scenario, including competing political and economic priorities, and future legislation that could undermine sustainability initiatives in the sector.

Table 1. Summary of Outcome Assessment and Portfolio Contribution

| Expected Outcome | Outcome Assessment and Portfolio Contribution | ||

| High-Level Outcomes | Partner organizations use project research to inform planning decisions and project development | H | Realized, clear portfolio contribution |

| Smallholders and women have improved representation in policy-making around oil palm | M | Partially realized, clear portfolio contribution. Relies on some theoretical extrapolation of the implication of policy changes. | |

| The research agenda on oil palm advances toward sustainability and inclusion | M | Partially realized, clear portfolio contribution | |

| Policy-makers recognize and reflect environmental sustainability and social inclusion in all oil palm-related policy | M | Partially realized, clear portfolio contribution | |

| Private sector adopts more sustainable and inclusive business models | L | Partially realized, clear portfolio contribution | |

| Accumulation of scholarship on oil palm influences organizational practice | L | Not realized, too early to assess. There is no evidence of realization. It is possible that portfolio research could indirectly contribute to practice change via portfolio influence on policy change. | |

| Smallholders and women have improved oil palm market access and share of benefits | L | Not realized, too early to assess. Realization of this outcome relies on the assumption that policies are effectively implemented and enforced. | |

| The oil palm sector (governments, private sector, NGOs, smallholders, CIFOR) develops more effective working arrangements | L | Partially realized, unclear portfolio contribution. Few respondents explicitly identified how the processes facilitated by the portfolio contributed to more effective working arrangements. | |

| Intermediate Outcomes | Government actors learn from oil palm research processes and findings | H | Realized, clear portfolio contribution

|

| Government actors build their capacities and relationships within the oil palm sector | M | Realized, clear project contribution

|

|

| Government actors engage CIFOR & partners to help make informed decisions on oil palm | M | Realized, clear project contribution

|

|

| Project partnerships facilitate mutual learning on oil palm | H | Realized, clear portfolio contribution | |

| Graduate students build their research capacities | H | Realized, clear portfolio contribution | |

| CIFOR & partners are recognized for expertise in oil palm research | H | Realized, clear portfolio contribution | |

| Private sector actors learn from oil palm research | L | Insufficient evidence, preliminary results indicate partial realization with clear portfolio contribution | |

| End-of-Project Outcomes | Policy-makers create new or adapt existing policy on oil palm (informed by research)

[EoP outcome] |

M | Realized, clear portfolio contribution

|

| Project partners & allies advocate for & pursue oil palm issues (using research)

[EoP outcome] |

H | Realized, clear portfolio contribution | |

| Graduate students continue careers in oil palm research to build on knowledge base

[EoP outcome] |

H | Realized, clear portfolio contribution | |

| Researchers use projects’ findings and methods

[EoP outcome] |

H | Realized, clear portfolio contribution | |

| Researchers pursue new questions on oil palm

[EoP outcome] |

M | Realized, clear portfolio contribution | |

| Private sector responds to (research-informed) policy change

[EoP outcome] |

L | Partially realized, clear portfolio contribution |

Evidence Rating: Low (L), Medium (M), High (H)

This article was written by Monica Evans.

This article was produced by the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA). FTA is the world’s largest research for development program to enhance the role of forests, trees and agroforestry in sustainable development and food security and to address climate change. CIFOR leads FTA in partnership with ICRAF, the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, CATIE, CIRAD, INBAR and TBI. FTA’s work is supported by the CGIAR Trust Fund.