In October 2015, more than 600 forest scientists and practitioners from 12 countries met in Bogor, Indonesia, for the Third International Conference of Indonesia’s Forestry Research (INAFOR). The Minister of Environment and Forestry and his senior staff were unable to attend because they were fighting the worst forest fires that the country had seen. In August, the World Agroforestry Centre published an ASB policy brief—Stopping haze when it rains: lessons learnt in 20 years of Alternatives-to-Slash-and-Burn research in Indonesia—which suggested that part of the problem was the short-term memory of the public and politicians: making promises in the midst of the smoke and haze but forgetting them as soon as rains have returned and the fires doused. ICRAF scientist Meine Van Noordwijk attended the conference as one of the keynote speakers. In this interview he explains his major concerns.Read his original blog at Agroforestry World Blog.

In October 2015, more than 600 forest scientists and practitioners from 12 countries met in Bogor, Indonesia, for the Third International Conference of Indonesia’s Forestry Research (INAFOR). The Minister of Environment and Forestry and his senior staff were unable to attend because they were fighting the worst forest fires that the country had seen. In August, the World Agroforestry Centre published an ASB policy brief—Stopping haze when it rains: lessons learnt in 20 years of Alternatives-to-Slash-and-Burn research in Indonesia—which suggested that part of the problem was the short-term memory of the public and politicians: making promises in the midst of the smoke and haze but forgetting them as soon as rains have returned and the fires doused. ICRAF scientist Meine Van Noordwijk attended the conference as one of the keynote speakers. In this interview he explains his major concerns.Read his original blog at Agroforestry World Blog.

What is your take on this year’s forest fires in Indonesia and what did you tell the conference?

The current fires have to do with Indonesia’s efforts to increase the production of timber and food, including oil palm. They are related to a dry extreme of the Indonesian climate in which water supply to agriculture and human use is scarce, beyond what our forests can buffer. This situation is exacerbated by climate change. Thus all the keywords in the title of the meeting have a direct relationship to the fires and haze.

But it is too easy to blame the fires on the El Niño event, even though it is on track to become worse than the worst-so-far, of 1997. And it is too easy to fall back into the old blame game of pointing to either smallholders or large plantations; clearly, both are involved.

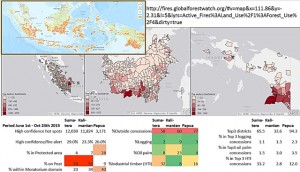

The open-access ForestWatch website suggests that the fires are highly concentrated: two-thirds of the fires in 3 Sumatra occurred in just three subdistricts, for example, with direct link to the expansion of fastwood plantations. Over 50% of fires on Sumatra and Kalimantan were on peat soils (and 9% of fires in Papua), 6–7% in protected areas (in Papua, 28%), and 23–34% in the areas supposedly protected by the moratorium (40% in Papua).

So who is to blame?

Under President Suharto, a one-million hectare scheme of peatland conversion was initiated in the name of food security. Under President Yudhoyono, a food estate was planned in Merauke, Papua, of at least one million hectares. It is no accident that these two areas are now among the hot spots of land-conversion fires that produce the haze. Where the government supports active and planned deforestation, it shouldn’t be surprised if local people add on to this.

On Sumatra, industrial timber dominates and three concessions in South Sumatra Province are responsible for one-third of all hot spots. In Kalimantan, the top three districts account for one-third of hot spots. 23% of fires are in oil-palm concessions but there are many companies involved. In Papua, 94% of hot spots is in three districts and industrial-timber plantations again are prominent but not as dominant as in Sumatra.

The policy shift of production forest to production of fastwood for the pulp and paper industries is closely linked with a lot of the land clearing fires. Yet, food security is not achieved and vulnerable groups suffer or even die from haze.

What does this crisis mean for Indonesia?

What does this crisis mean for Indonesia?

It seems that the idea of carbon finance has lulled the Indonesian public debate into such a state that the current haze can be blamed on lack of delivery on the REDD+ promise.

In 1997/8, the economic damage of the haze to health and public welfare was estimated to be about USD 20 billion, of the same order of magnitude of the gross annual value of Indonesian palm-oil exports. When divided by the estimated carbon emissions, this translates to a cost to Indonesian society of 50–100 $/tCO2. This cost is more than tenfold what carbon markets were expected to bring to Indonesia, but they never did. Somehow Indonesian society accepts huge losses to its own people’s wellbeing, while looking for much smaller international funding streams to shift the balance.

Also, the energy of the biomass lost in these fires, if harnessed properly, could more than meet Indonesia’s energy requirements.

What is your take away from the conference?

Self-sufficiency in food, energy, timber and water will not come to Indonesia until these issues take centre stage in the local elections and in national policy discourse. Current forestry research in Indonesia can do little to achieve the valid target of the INAFOR meeting but at least the discussions in October opened a wider debate.